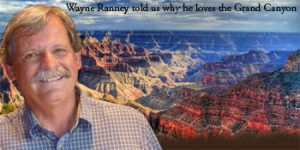

Our block trainings also bring in outside experts sharing their perspectives, and this year was no exception. We learned about fundraising in New York — and fun-raising in the Grand Canyon!

Tracy Boak, an attorney in the New York firm of Perlman & Perlman, described legal issues that nonprofits should watch out for to avoid triggering an investigation by state attorneys general. Boak previously served as a state charity regulator, as director of the Pennsylvania Bureau of Charitable Organizations where she oversaw the Commonwealth’s charitable solicitation law.

Boak now helps nonprofits navigate the maze of charitable fundraising regulations. “My job is to help charities to get out of trouble,” she said. “It’s challenging work but I love it.”

With nonprofits facing increased scrutiny due to “sham charities,” Boak outlined several red flags that could trigger an investigation:

Missing deadline dates: Waiting until the last day of an extension period to file federal 990 forms almost always guarantees missing the deadline for filing these forms with the state, especially for nonprofits operating in several states. Some nonprofit leaders mistakenly believe that because the 990 is a federal form it’s not applicable to state laws. In reality, she said, if state law requires the submission of the 990 it is considered a legal document for state enforcement purposes and information in the 990 can be used against the charity in a prosecution.

Making mistakes: When you sign off on the 990 you do so under penalty of perjury; information reported in one section that is inconsistent with another section can trigger an alert. Some attorneys general aggressively pursue nonprofit fraud and are less willing to excuse what may have been an honest mistake. “Make sure that all parts of your 990 are consistent. Tiny little details are important and they can flag you for a review,” she said. It’s relatively simple to identify charities that are clearly fraudulent. “But it’s when people don’t know what they don’t know, they’re the ones more likely to get into trouble and the attorney general will be more likely to come after them.”

Fundraising expenses: Even though the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that spending money on fundraising is not intrinsically wrong, excessive costs may be perceived by some attorneys general as a potential indicator of fraud.

Misunderstanding charitable solicitation rules: The interpretation of what constitutes a charitable request is very broad in some states, and anything that passes for an appeal to aid a charitable cause may be considered a solicitation.

Failure to comply with donor-implied restrictions: State regulators may have a stricter interpretation than the donor. For example, donations for a specific project or campaign may be seen as fraud if they were not used for that purpose.

“Cause marketing”: Corporate entities may donate a portion of sales to a charity, but nonprofits are not allowed to promote those sales at the risk of exposure to the Unrelated Business Income Tax. “Even though the sales are for their benefit, this is advertising for the corporate entity,” Boak said. Nonprofits can acknowledge the gifts and thank the corporation but cannot directly encourage sales.

Joint cost allocations: An ongoing challenge is to determine the portions of expenses that can be allocated to program and education or fundraising. Allocations for education must include a call to action in order to be acceptable, she said.

Not meeting the public support test: If all of a nonprofit’s funding comes from a single donor, especially if that donor is a relative of the founder, the organization may lose its status as a public charity and be treated instead as a private foundation.

Conflicts of interest: Awarding a contract for services to the business of a board member might be considered a conflicted transaction under some state laws. “It might be the best deal for the organization but you have to go through all the steps to prove that it is,” Boak said. The nonprofit should solicit bids from other firms and verify that this is the best option, and the board member cannot participate in the discussions. The organization should have a conflict-of-interest policy.

Introduction to Federal Audits

“Suddenly finding out at the end of the year that you have to have a single audit is not a situation anybody wants to be in,” he said.

Since 2014, the federal government has required a “single audit”, a thorough, organization-wide examination of any nonprofit or state or local government entity that expends more than $750,000 in federal awards, to ensure that the public’s money is being spent appropriately. Organizations receiving less than the $750,000 threshold are required to adhere to all compliance regulations as well. The audit applies to entities that receive grants either directly or indirectly in the form of pass-through grants funneled through state or local governments. Nonprofits need to ask and know where the money came from, Watson said.

The Office of Management & Budget’s Uniform Guidance code of federal regulations addresses federal expenditures by nonprofits. While regular audits follow generally accepted accounting principles, single audits adhere to both GAAP and the Uniform Guidance standards. Single audits therefore take more time, involve more forms and schedules, and are more complex to test internal controls and review entity-wide weaknesses, deficiencies and compliance.

Watson identified common findings regarding nonprofits’ compliance with the Uniform Guidance. These include:

- Conducting allowed and unallowed activities

- Cash management

- Allowable costs and cost principles

- Eligibility of individuals and organizations receiving assistance

- Compliance with matching, level-of-effort or earmarking requirements

- Management of equipment and real property

- Adherence to the period of performance by which time the funds must be expended

- Procurement, suspension and debarment provisions ensuring that purchases of goods and services and the selection of vendors comply with federal requirements. There may be different standards for small purchases, micro-purchases, sealed bids, competitive proposals, and sole-source procurement.

- Program income being reported and calculated accurately and timely

- Time and distribution records that accurately reflect the work performed by all employees whose salaries are paid in whole or in part with federal funds.

Why We Love the Grand Canyon